MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker 03/2023

03/2023

by Helena Legarda

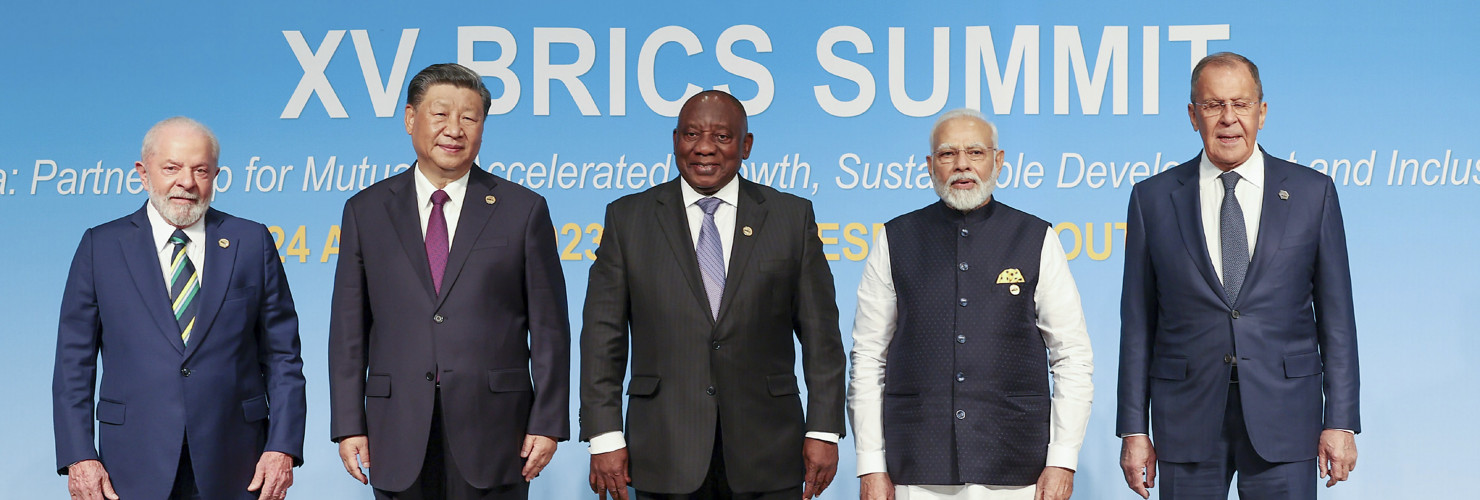

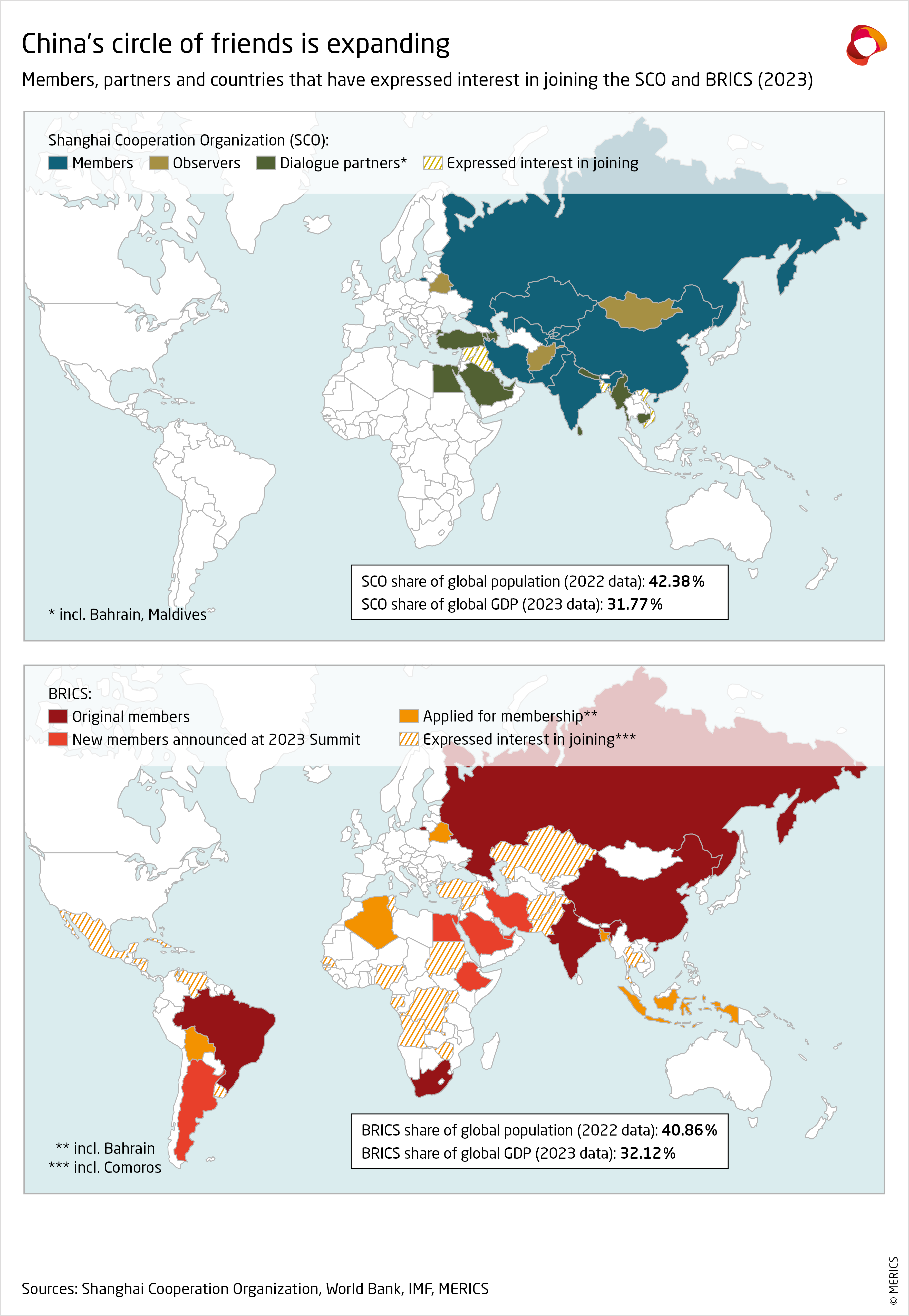

To build a counterweight to international institutions seen as too Western-dominated, Beijing wants to expand the BRICS grouping and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Chinese officials expressed strong support for adding new members to both organizations in the months leading up to two summer summits – the July SCO summit hosted by India (whose full members are four ex-Soviet border states plus India, Pakistan, Russia, China and now Iran)1 and the August BRICS summit of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa in Johannesburg.2 Beijing’s efforts within BRICS were successful. At the summit in South Africa, the group announced six new members that will join starting January 1, 2024: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Beijing’s push to expand BRICS and the SCO shows it puts renewed importance on these multilateral fora amid worsening geopolitical competition with the United States. They form part of its drive to strengthen ties with nations in the Global South. Beijing, and Moscow, are actively reaching out to countries that do not see themselves as important players in the current order to offer an alternative and a counterweight.

The BRICS and SCO are often dismissed as little more than talking shops with no clear identity or agenda. Yet the fact that dozens of countries, such as Bangladesh, Argentina or Indonesia, are reportedly seeking to join either or both groupings confirms their attractiveness.3

The SCO has a particular focus on expanding in the Middle East, while BRICS is also targeting nations across Africa and Latin America. Becoming part of a smaller club of non-Western countries with growing influence, where their voices are likely to carry more weight, is an attractive proposition for many developing economies seeking to increase their global status.

Unconstrained by agreed norms and principles, the two groupings can serve as a diplomatic and geopolitical lifeline for members who find themselves internationally isolated. Moscow has benefitted greatly from this since launching all-out war in Ukraine in February 2022. Barred from traveling to much of the Western world, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin’s international trips in 2022 were mostly to other SCO member countries. And both the SCO and BRICS have emphasized that he will not be uninvited from their summits – a fact that Moscow has used to criticize the West’s failure to isolate Russia.

However, potential members are motivated by positive opportunities too. As BRICS cooperation gathers pace and the SCO’s focus expands from security to energy and economic issues, they hope that membership will generate economic opportunities and privileged access to China. Amid talk of diversification and de-risking in Europe and the United States, the pull of China’s market remains strong across the Global South.

The climate of geopolitical competition means joining BRICS or the SCO may carry costs. First, neither organization can provide full alternatives to existing alliances or multilateral organizations. BRICS may have the ambition of becoming an alternative to the G7,4 advancing initiatives like the New Development Bank or the BRICS payment system. But the SCO is neither a security provider nor an alliance, and shows no intention of becoming one. The duo are, for now, forums for dialogue and the expansion of bilateral ties and operate mostly in the normative and geopolitical space.

Many developing countries may find themselves in a difficult balancing act between closer engagement with the SCO and BRICS and preserving their vital security and economic ties with Western partners. Turkey is an example here, a NATO ally that has faced strong pushback over its stated ambition to join the SCO.5

The balancing act may have been easier in the past, but worsening geopolitical competition and deepening mistrust are making it harder. China’s role in these organizations has long been a source of concern for Western nations. But the war in Ukraine means tensions have also begun to emerge over Russia’s role and presence.

For instance, South Africa felt the pressure as it prepared to host this year’s BRICS summit. Pretoria spent months equivocating on whether Russia’s President Vladimir Putin would attend in person. The existence of an International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrant for Putin put the South African government in a bind. As a signatory of the Rome statute, Pretoria is legally obliged to arrest individuals indicted by the ICC, so failing to do so would make South Africa look like it was taking a clear geopolitical side. But uninviting Putin could damage its ties with the rest of the BRICS group.6

Moscow and Pretoria eventually agreed Putin would not attend in person. But there are clearly costs associated to appearing too close to China or Russia – and by extension to the BRICS or SCO. However, the benefits of joining seem to outweigh any costs for many nations.

Not all members are equally keen on expansion. Within BRICS, India and Brazil seem especially wary of a bigger pool that would dilute the power and say of existing members.7 Despite these concerns, an expansion of the group was agreed upon at the South Africa summit. China’s expansion drive, however, might antagonize some, worsening the internal dynamics.

Risks also lie in recruiting countries with unresolved bilateral issues (as with India and Pakistan within the SCO) as this could block consensus and hinder action. The SCO has found a workaround to internal tensions by issuing statements or strategies not signed by all members.8 But this is not a sustainable solution in the long run.

As the EU can attest, rapid expansion can also create difficulties in crafting an organizational identity, ideology and overarching goal amid new national interests and areas of concern. Although neither SCO nor BRICS members are currently joined together by a common ideology, they do share a desire to play a greater role in a reformed global order that better reflects and responds to the needs of emerging economies.

As part of China’s push to build a network of “like-minded partners”9 in the Global South and reform the global order, BRICS and the SCO also have a role in disseminating policies, concepts and approaches that clash with European interests and values.

Beijing is actively pushing the Global Security Initiative (GSI) and Global Development Initiatives (GDI) within these bodies to propagate its approach to global security and view of the security-development nexus (i.e., security as a precondition for development). Beijing previously succeeded in exporting its concept of the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism and extremism, making it a core task of SCO in 2001.10 This extremely broad slogan is used to promote and justify repression in Xinjiang and to rally support among China’s western neighbors.

Russia’s diminished international status means China could become the main rule-setter in groups that represent a large percentage of the world’s population and economy. Already, both BRICS and the SCO (separately and without taking into account membership overlaps) represent more than 40 percent of the world’s population and more than 30 percent of global GDP.

Europe must not lose sight of this trend. Many countries in the Global South see membership of these groups as an opportunity for a louder international voice, even if they do not share all their values. The EU would do well to acknowledge these concerns and do more to become a more attractive partner. should dedicate more resources to strengthening its partner relationships globally, and move beyond the dichotomy of democracies versus authoritarian states, to prevent further fragmentation of the global order.

China’s slow recovery from its strict zero-Covid policies is piling up socio-economic stress, from rising inequalities, high unemployment rates and increasing pressure on households.

Young people especially are losing confidence in their future, faced with record youth unemployment (21.3 percent in June, after which the National Bureau of Statistics said it would suspend publication of urban youth jobless data), unattractive working conditions, an unsustainable housing market and rising prices. The poor outlook has prompted many households to economize, slowing the economic rebound.

China’s ageing population puts additional pressure on its social system. Families shoulder the burden of care, putting a disproportionate extra workload onto women and limiting their capacity to work full-time. Many decide against having one or more children, which further exacerbates demographic change.