China’s global debt holdings are increasingly a liability for Beijing

No. 2, July 2023

Just as China’s economic recovery has proven lackluster, so too has much of China’s economic engagement with the rest of world sputtered along in Q2 of 2023. In this edition of the MERICS China Global Competition Tracker, our experts look into three different issues that reflect Beijing’s struggle on the international stage, some of its successes, and the challenges and opportunities facing some of its national champions as they look overseas for future growth.

In our top story, MERICS Analysts Francesca Ghiretti and François Chimits look into China’s now massive role in developing country debt holding at a critical moment. As developing countries emerge from the pandemic with massive debt burdens, an international effort by creditors to restructure debt for the worst affected countries, and to write off some of the burden, stalled because of Beijing’s inaction. As our experts indicate, China is the linchpin of the issue, and the longer that it holds back progress on debt relief/restructuring talks, the greater the risks become for the debtor countries, the lending countries, and the global economy as a whole. What Beijing does next could have massive real-world implications for many, but most of all for China’s reputation, let alone its own financial stability.

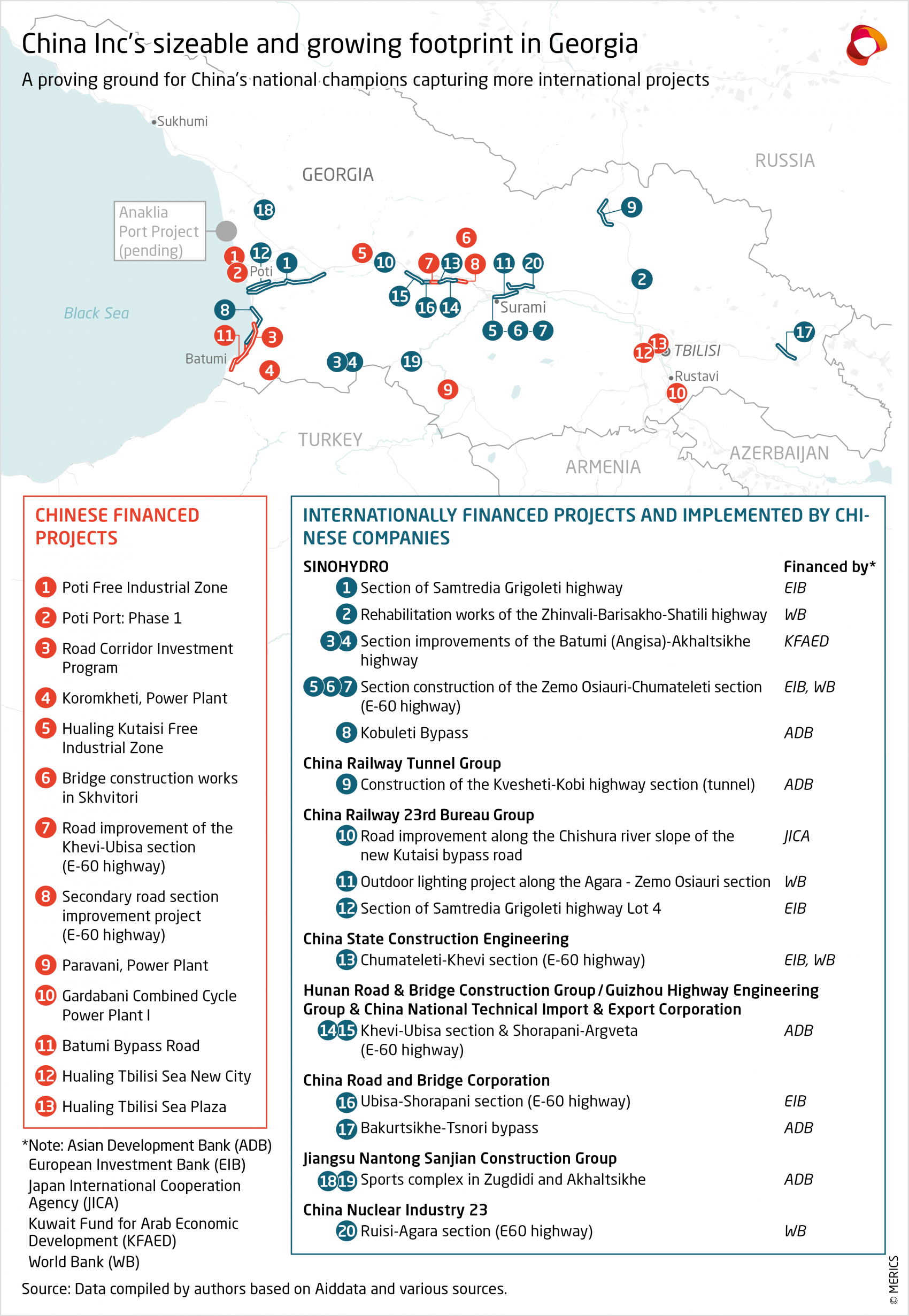

Meanwhile, our regional spotlight covered by MERICS Analyst Aya Adachi examines China’s activities in Georgia. The country has surged in its importance for many key infrastructure projects related to the ‘middle corridor’, a transportation route that stays on the south side of Russia – which has become more viable in a post-Russian-invasion world. While concerns abound regarding fairness and corruption for projects in the country in general, it is also the case that many of the projects that China’s own companies are leading on are not connected to the BRI, but are instead financed by mulit-lateral development banks. The situation is further complicated by Georgia’s status as an EU member state candidate, as critical infrastructure projects built and often managed by Chinese SOEs could someday be absorbed into the EU if Georgia can accede.

Finally, MERICS Senior Analyst Jacob Gunter covers China’s main nuclear energy companies in his Key Players segment. Having spent decades trying to catch up to European, Russian, and North American nuclear energy technology, China’s own nuclear champions are attempting to cement themselves overseas. However, these players are facing limitations abroad, in part due to the sheer demand for nuclear reactors in their home market (which sucks up much of the supply that China’s companies can fulfil), but their domestically developed Hualong One reactor design has yet to build up a track record to compete with long-established competitors’ designs. Instead of an immediate source of competition to European industry, like in the EV sector, the nuclear energy sector represents a medium to long term competition risk to European players. However, even then, China’s nuclear energy champions will be competing with a growing array of renewable and green energy types, so their success in capturing global nuclear market share is far from certain.

The Middle Corridor from China to Europe through Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey could provide an alternative route for Chinese goods to reach Europe without passing through Russia. Since President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU and European companies have been reinvigorating their policies towards the South Caucasus and Central Asia and are now pushing for the expansion of the “Middle Corridor”.

Georgia’s government manages its strategic position carefully by engaging with multiple players to balance its vulnerable location on Russia's border. China and Chinese companies have risen as prominent actors through investments, Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and also as contractors building infrastructure projects funded by others.

Today, Georgia is trying to revive its economy by leveraging its geographic position between Europe and Asia, Russia and the Middle East to become a global trade and manufacturing hub, re-enacting a modern version of its historical role serving the original ‘Silk Road’ and Black Sea ports.

Georgia has gained plaudits for creating a smooth business environment. In 2007, the World Bank named Georgia “the number one economic reformer in the world”. Between 2007 to 2008, Georgia’s ranking for ease of doing business rose from 112 to 18. By 2020, Georgia had climbed to seventh place. To attract investors and lenders, the government has hosted the Silk Road Forum and made Georgia the most active country in the Caucasus region in signing Free Trade Agreements with major players, namely, EU, China, Turkey, and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

In contrast to nearby countries, Georgia has been pro EU and pro-US, as seen in its eagerness to join the EU, its involvement in Iraq War and in the US-led mission in Afghanistan. However, Georgia must reckon with Russia’s strong regional influence and a Russian occupation in some of its territory; this has limited its room to maneuver with neighboring countries and ability to promote the Middle Corridor. To counter Russian influence, Georgia has increasingly turned to China to supplement its engagement with the EU and United States.

In the past eight years, Georgia-China relations gained have pace: in 2015, the privately-owned Hualing Group made the biggest Chinese investment in Georgia to date; Georgia joined BRI in 2016; and swiftly agreed a bilateral FTA in 2017, the region’s first. China-Georgia trade volumes rose from USD 362.2 million to USD 1.9 billion between 2010 and 2022. In the same period, China’s share of Georgia’s total imports rose from 6 percent to 8 percent, while its share of total exports rose from 2 percent to 13 percent. It is now among Georgia’s top three trade partners, after Turkey and Russia.

China has helped finance 13 projects in Georgia (see map), such as roads and powerplants and two strategically located zones. The Poti Free Industrial Zone is a manufacturing base near Poti Port on the eastern Black Sea, which has been 75 percent owned by CEFC (Euro-Asian) LLC China, a subsidiary of China’s giant private firm, CEFC Energy since 2017. The United Arab Emirates’ Ras Al Khaimah’s owns 15 percent and Georgia 10 percent. Hualing Free Industry Zone in Kutaisi is under the direction of Hualing Group, which took the management of the new zone in 2015 for 30 years with plans to invest USD 30 million over time. The zone is seen as a connecting hub between Kutaisi International Airport, Poti port and the capital city, Tbilisi.

Georgia has received fewer Chinese development finance projects than some Middle Corridor countries (Azerbaijan and Turkey) though significantly more than Armenia. Despite Georgia’s appeal as a potential economic hub, it has not been a BRI priority.

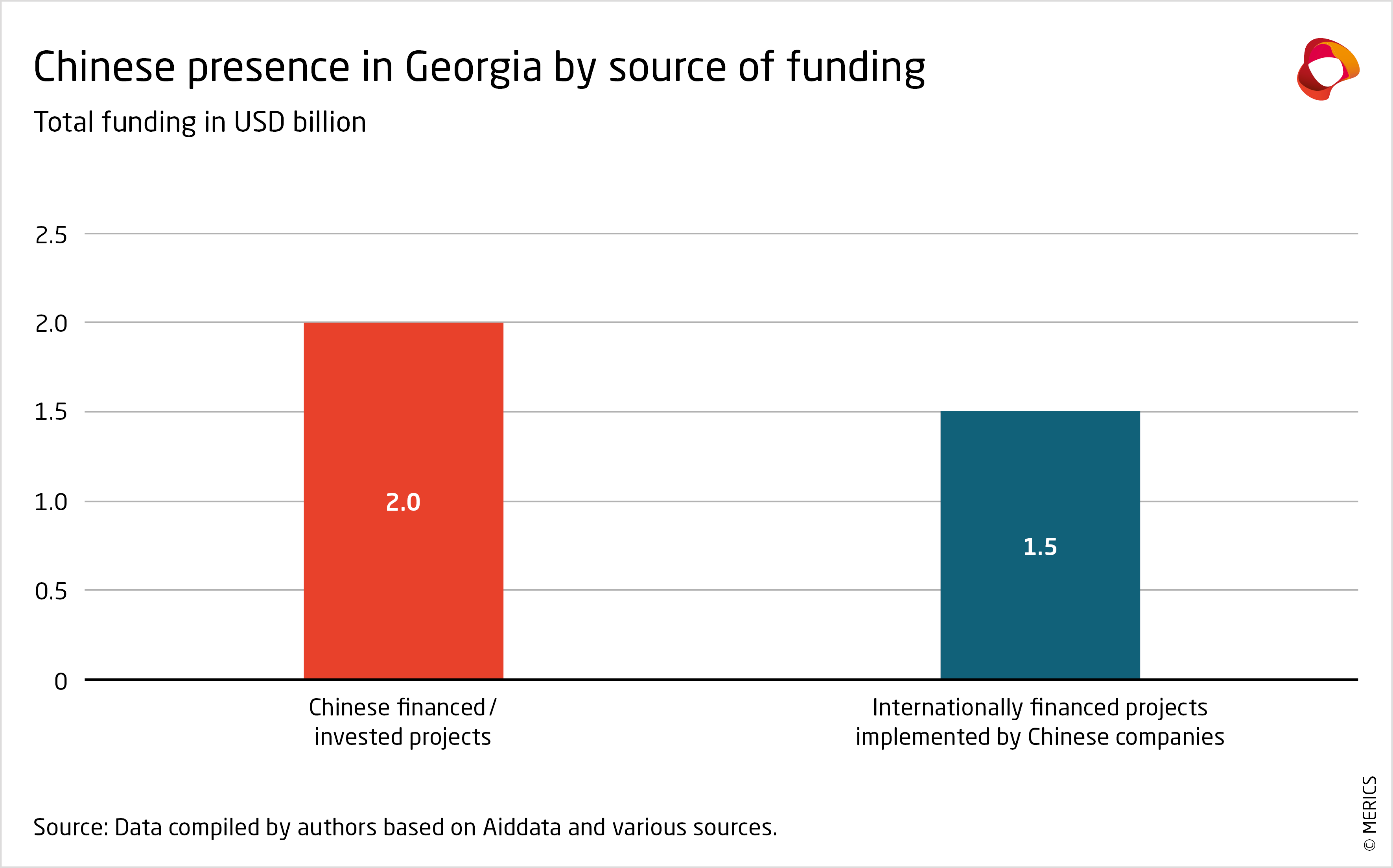

Chinese companies have won tenders on 20 infrastructure projects funded by international financial institutions (IFIs), including the European Investment Bank (EIB), World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB). The sheer number of such deals in Georgia is striking, although such contracts exist elsewhere (e.g., Croatia’s Pelješac Bridge and the Solomon Islands port project). In Georgia, Chinese companies are involved in deals worth a total of USD 3.5 billion, of which 43 percent are financed through credits provided by IFIs to the Georgian government and the rest is Chinese funded (see exhibit).

Georgia’s Ministry of Infrastructure has said Chinese firms have done well because European companies “are mostly unable to compete with large Chinese companies in terms of qualification and price” as well as “experience”. But some Chinese companies that won tenders managed by the Georgian government have a record of mismanaged projects and corruption or ended up on international blacklists by IFIs, including WB, African Development Bank, International Monetary Fund.

Overall, China Inc has thus far met few hurdles to operating in Georgia where it is met by weak state institutions and private interests significantly influencing decision-making processes, which has been termed “state capture”. Observers have pointed out that Georgian authorities have exhibited a striking disregard for due diligence measures in their dealings with China, even in even in sensitive industries.

Despite being the shortest route between western China and Europe, many logistical barriers stand in the way of the Middle corridor becoming a success. First, trade movements take longer due to the transshipments from train to ships at the Caspian and Black Sea. Transits through multiple small countries that have yet to synchronize and harmonize their import and export procedures add to difficulties.

Second, regional instability in the South Caucasus and Georgia’s own problems can discourage investments and slow progress. The ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Russian occupation of Georgian territory and instability in Afghanistan are all sources of volatility. The conflict between Georgia’s neighbors and their allies – Armenia backed by Iran and Russia is set against Azerbaijan supported by Turkey and Israel – remains deadlocked, despite US and EU mediation attempts in May 2023.

Finally, prospects for the success of the Middle Corridor depend on whether the stalled Anaklia Port Project can be brought to life. Considered the only location for a new deep seaport on the eastern Black Sea, it could be a game-changer by increasing trade capacity to create a viable route. Plans from a US-Georgian consortium remain stalled due to pressure on Georgian elites from Russian interests objecting that a deep sea port could host NATO ships and compete with Novorossiysk port in southern Russia.

Obstacles remain significant. But diversifying trade routes away from Russia is now of strong interest to corporates and to regional and external government stakeholders. Georgia and neighboring states have ramped up inter-state cooperation since Russia’s assault on Ukraine and signed memorandums on railway cooperation and trade facilitation. In March 2022, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Kazakhstan produced a quadrilateral statement on the need to develop the Trans-Caspian International Transport Corridor (TCITC), also known as the Middle Corridor.

European rail and shipping companies have swiftly put their Middle Corridor services in motion. The Netherland’s Rail Bridge Cargo, Danish shipping corporation Maersk, Finland’s Nurminen Logistics, Georgia’s state railway company and a joint effort by Austrian OBB Rail Cargo Group and Dutch Cabooter Group all started services between China and Europe via the Middle Corridor – some within weeks after Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

The results are visible: cargo shipments along the Middle Corridor swelled tenfold from 350,000 metric tons and 530,000 in 2020 and 2021 to 3.2 million metric tons in 2022. But the middle route’s overall capacity remains low compared to the northern route via Russia’s Trans-Siberian railway, which moved 144 metric million tons of cargo in 2020. The southern sea route from China is projected to carry more than one billion metric tons in 2023. However, the rapid increase in Middle Corridor trade shows its potential, despite low overall tonnage.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Beijing does not appear to have changed its approach to the South Caucasus. Beijing’s recent announcement that construction would start on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway indicates China continues to prioritize Central Asia. While Beijing chooses to focus on the eastern sections of the Middle Corridor, Europe appears to be closing in on its commitment in the South Caucasus.

The EU has a pressing interest in engagement and stability in the South Caucasus. In 2022, it gave Georgia a roadmap of reforms needed to gain EU candidate status, and it is trying to mediate between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Specific moves to enhance the Middle Corridor include a planned undersea cable to improve connectivity to Georgia and reduce dependence on lines through Russia, amid concerns about global data infrastructure.

However, the EU has struggled to improve cooperation with Georgia, which has preferred working with Chinese companies that have been enabling partners for corruption. For Georgia’s government, China is a key actor, as long as Beijing remains ambiguous on Russia and offers economic opportunities. Opinion polls in Georgia show neutral public attitudes towards Chinese investment overall. This could quickly change if Beijing were to increase its support for Moscow, as anything that bolsters Russian power is a red line for Georgians. For Beijing, the question is whether it has enough leverage over Moscow to make Russia accept growing Chinese influence in the region without fully supporting Russia’s position in the South Caucasus. The EU and European companies looking into recalibrate their positions in Georgia should use opportunities to challenge of potential changing perception of China linked to its ambiguous dynamic with Russia.